CHICAGO — Eddie Johnson was almost done with his run, and he wanted to finish strong. So with legs pumping, head down, the lanky forward from Westinghouse High School pushed hard down a back street in the West Side neighborhood where he spent his teenage years.

He sprinted until he got the sense that, hmm, he no longer was alone.

“I ran into a gang meeting, it was probably 1,000 guys deep,” Johnson said. “They looked at me, and some of them were getting ready to get physical.”

Yikes. From what he describes, you conjure up Cyrus and the “Can you dig it?!” scene from “The Warriors.” Only instead of the Baseball Furies or the Rogues, this was real. Maybe the Vice Lords. Or the Four Corner Hustlers, just a couple of the street gangs prominent in the city’s “L-Town” area.

Then something strange happened: Nothing.

“About 10 guys in the crowd noticed me and knew what I was doing,” Johnson recalled. “They let me go through. ‘Don’t bother him,’ guys were telling other guys. They knew I had an opportunity to do something. And they didn’t bother me.”

Johnson got a pass that day. Enough of the hard cases in the crowd respected the dream he was chasing — from Westinghouse to the University of Illinois to the NBA, where he played 17 seasons and scored 19,202 points — that they cut him slack, same as they have for players before and in the four decades since.

It’s a sign of the reverence vast segments of the local population have for the sport, the high regard that bolsters a case made constantly by players and coaches with roots here. More than any other city in the nation, they contend Chicago is the “Mecca of basketball.”

With NBA All-Star 2020 descending on United Center (home of the Bulls) and Wintrust Arena (where DePaul University’s teams and the WNBA’s Chicago Sky play) this week, a familiar refrain that Chicago might be the center of basketball’s universe packs some extra context and credibility. Not that certain proponents ever are shy about making the claim.

“In Chicago, it means a lot more to us because we are a basketball city and we are the Mecca of basketball, and you can quote me on that,” Lakers big man Anthony Davis said back in July.

Anthony Davis “Chicago is the Mecca of basketball and you can quote me on that” pic.twitter.com/NfuLAxYMMZ

— Tony Gill (@thetonygill) July 19, 2019

A product of the Englewood neighborhood on the South Side, Davis was back in town to work with a Nike youth camp for kids ages 8-17. He hadn’t participated in anything like that in his grade school years, coming up the grittier Chicago way, indoors or (most of the time) out.

“It’s basketball in any condition, you know you gonna find a way to play,” Davis told a gathering of reporters. “No matter if it’s hot, it’s freezing cold in the gym, outside it’s raining, whatever. … By any means necessary, we wanna play the game.”

Clippers coach Doc Rivers, a high school All-American from just outside the city limits in Maywood, Ill., backed Davis’ take entirely.

“Yeah, he’s right. It’s not even a question,” Rivers said. “The Mecca of basketball is absolutely Chicago players. New York gets all the rub, which I don’t get, but Chicago, it’s not even close.”

The talent pipeline that delivered everyone from George Mikan and Cazzie Russell to Jabari Parker and Davis was pumping particularly well during Rivers’ heyday.

“You play against everybody,” Rivers said. “I mean, how many kids can say, unless you grew up in Chicago, you can have a pickup game out in the park with Isiah Thomas, Terry Cummings, Maurice Cheeks, Mark Aguirre, Darrell Walker. There’s not a lot of pickup games like that in your same grade. That’s every year. That’s called Chicago basketball.”

Look, this is highly subjective and largely recreational. Basketball fans across the country can argue for their towns as Meccas and no one is going to break the ties.

New York? Of course. Los Angeles is the glamour market of the NBA, the site of so many players’ offseason homes and training regimens. Boston, Philadelphia and Detroit can muster cases too. And if this version of the debate weren’t so NBA-centric, Indiana and North Carolina might try to crash the party as state entries.

But this is Chicago’s time to shine. And to brag.

How many kids can say, unless you grew up in Chicago, you can have a pickup game out in the park with Isiah Thomas, Terry Cummings, Maurice Cheeks, Mark Aguirre, Darrell Walker. …That’s called Chicago basketball.”

Clippers coach and Chicago native Doc Rivers

“Look at how many players we’ve put in the league,” said former NBA swingman Kendall Gill, raised just south of the city in Olympia Fields. “It’s like we never stop sending guys to the league.”

With each one, the fraternity grows. “Definitely,” Gill said. “When Dwyane Wade was first in the league, I was at the end of my career. But when he saw me, he said ‘Hey Chi-town.’ And I said, ‘Hey, what’s up young fella?’ The young players know about the guys before them, and it’s always going to be repeated.”

The city has a hoops history that can offer compelling evidence for Mecca status. Consider:

- In 1893, 15 months after Dr. James Naismith invented the game, Chicago formed its first basketball league with a group of YMCA teams.

- Englewood, where Davis and Derrick Rose grew up, became in 1899 home to the first permanent high school boys team.

- The Harlem Globetrotters actually began life in 1926 on Chicago’s South Side and were known as the Savoy Big Five (named for the ballroom where they played). Their founder, Abe Sapterstin, soon changed the name to emphasize the black heritage of the team — yet the ‘Trotters didn’t play a game in Harlem until 1968.

- George Mikan, of Joliet, Ill., dominated college basketball while at DePaul, then did the same as the NBA’s first superstar. Talk about a game-changer — the 6-foot-10 Mikan had the league scrambling to cope in its early years, imposing or altering rules to widen the lane, whistle 3-second defensive violations and prohibit goaltending. Fittingly, he and Doc Naismith walked into the Hall of Fame in 1959, the first year it opened for business.

- Cazzie Russell was a local legend from Carver High who starred at Michigan, then joined the Knicks as the No. 1 overall pick in 1966. Russell and New York won an NBA championship in 1970. Two years later, Chicagoans cheered as he made the All-Star Game while with Golden State.

- The Chicago Stags disbanded in 1950 after four seasons. The Chicago Packers-turned-Zephyrs lasted two years before moving to Baltimore in 1963. But when the Bulls were created in 1966, they stuck. More than that, they became the only NBA expansion team to reach the playoffs, going 33-48 while coached by Chicago favorite and Tilden High grad Johnny “Red” Kerr.

The Bulls weren’t an instant hit with paying customers, but by their fourth season, they had assembled the nucleus of a contender that reached the conference semifinals or finals for five consecutive seasons. They won no titles, but the crew of Jerry Sloan, Norm Van Lier, Bob Love, Chet Walker and Tom Boerwinkle played some of the fiercest, most exciting games in franchise history. Until 1984 or thereabouts.

“Tickets were very easy to come by,” said Johnson, who was 12 when his mother moved the family from the Cabrini Green housing projects closer to Chicago Stadium. “Bob Love and Chet Walker were guys that I idolized growing up — Love was so smooth, and Walker with his 55 pump fakes.”

- In 2012, Rose (Simeon), leading the Bulls in his hometown, became the youngest MVP in NBA history. Davis, after leading Kentucky to the NCAA title in his lone season in Lexington, was the consensus choice to be drafted first overall by the New Orleans Pelicans. And though only a junior (Simeon also), Parker already was generating buzz as the nation’s most coveted high school star. So the top players, on three different levels, were all from the South Side.

More than a decade earlier, Tony Allen had laid the foundation for his 14-year NBA career at Crane High in the Chicago Public League. He praised the summer leagues in the city for developing talent and whipping up excitement.

“Man, just to back up what AD said, we’ve got an infamous Pro-Am league,” Allen told NBA.com. “It was just some of the best ballplayers you could name that came through and played. Don’t forget about our infamous documentary story, the Arthur Agee story [“Hoop Dreams” documentary] … We were the first ones to put reality TV on the basketball side of things.”

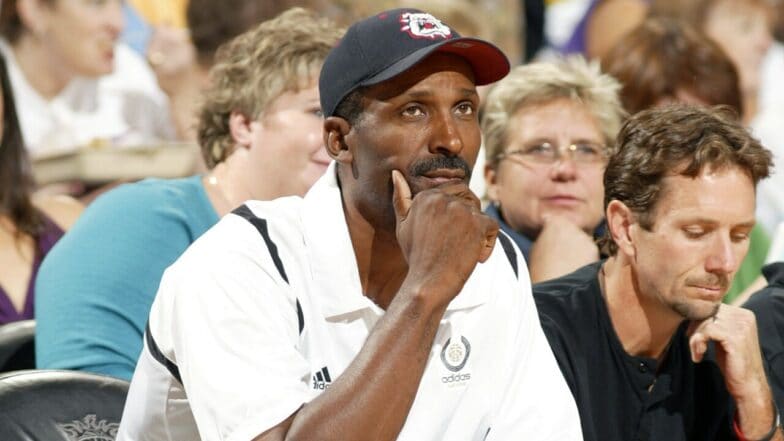

Johnson, longtime broadcast analyst for the Phoenix Suns and a co-host on Sirius XM’s NBA channel, also shared memories of summer basketball, dating back to the league at Malcolm X College. Then it was Chicago State, and later, as his pro career unfolded, Illinois Institute of Technology.

“I tell you, the gym was packed every night and you had the best of the best playing there,” Johnson said. “Every NBA player who was from Chicago would come back and play there. It kept us in shape, but it was a tremendous environment because it was packed.”

Especially from 1987 to 1989, when Michael Jordan came back to town and played — and notably in his final appearance. Shelly Stark, described by Johnson as a cornerstone of Chicago’s summer-league offerings, was there the night Jordan locked horns with a young Tim Hardaway. Hardaway, another South Sider and son of Chicago playground “legend” Donald Hardaway, had wrapped up at Texas-El Paso and was headed to Golden State.

“But on the South Side Tim was huge, and, man, you should have been there for that game,” Stark told the Chicago Reader in 2003. “We had people coming in from all over, lining up outside the door, to see MJ and Hardaway free of charge.”

Stark said each player scored 45 points and Jordan’s team won by two.

Jordan’s impact in growing basketball’s popularity in Chicago is undeniable. The season before he was drafted, in a Bears and Cubs town, the Bulls drew an average of 6,365 fans. In Jordan’s first two seasons, that bumped to about 11,600 per game, with about 7,000 unsold seats most nights in the cavernous Stadium. But by 1987-88, attendance had nearly tripled in four years to 18,061.

NBA commissioner Adam Silver was studying at the University of Chicago during Jordan’s early years. “Prior to that 1988 NBA All-Star game [at the Stadium],” Silver recently told NBC Sports Chicago, “I attended lots of games with my friends in law school. My recollection is it was not difficult to get tickets. Even for the great Michael Jordan, you could go to the ticket window before the game.”

In the 1990s, though, the Bulls broke through, winning six championships in eight seasons with Jordan, Scottie Pippen, Phil Jackson and the rest. Kids throughout the country wanted to “Be Like Mike,” but nowhere more than in Chicago.

“Michael Jordan came up and put those championships in our city, and showed our own youth, man,” said Allen, who was nine when the first 3-peat started and 16 when the second one ended. “I remember running outside and everybody just going crazy. That motivated cats like myself and players all over the world.”

Still, Jordan was born in Brooklyn (he turns 57 on Feb. 17). His family soon moved to Wilmington, N.C. He doesn’t qualify for any all-time, All-Chicago team. Neither, for that matter, does Love, Walker, Pippen or Dennis Rodman.

Same with Kevin Garnett, who tore it up in his one year at Farragut Academy — the nation’s No. 1 prospect, leading to a Hall of Fame-worthy NBA career — but spent his first 17 years in Mauldin, S.C.

No, the best to ever come from and represent Chicago have deeper roots. Like Aguirre, Cummings, Davis, Wade and Rose. And Thomas.

“Isiah, he took it to a new level,” Johnson said. “He was a true prodigy. His ball handling, his persona, all as a young man. I played him 1-on-1 when he was in eighth grade and I was a junior, and he almost beat me. I had to be real physical with him to beat him.”

Thomas checked all the boxes of Chicago basketball bona fides. He was one of nine children, raised by his mother Mary on the West Side, not far from the asphalt court at Gladys Park. Money was tight, food was scarce. Mary Thomas became the stuff of legends and made-for-TV movies when she faced down, with a sawed-off shotgun, a group of Vice Lords who had come knocking to recruit her sons.

Seeking better for her youngest son, she steered Thomas to the suburb of Westchester — a 90-minute commute each way by bus and train — to St. Joseph’s High School. That’s where he starred and earned a scholarship to Indiana, where he took coach Bob Knight and the Hoosiers to the NCAA title as a sophomore in 1981.

Now imagine Rose getting drafted by the Pistons instead of the Bulls in 2008. That’s essentially what happened with Thomas in 1981, when Detroit selected him second overall in the Draft, four spots ahead of Chicago. The most successful player in the city’s history — 12-time All-Star, two championships, Hall of Fame — wound up exiled to a rival, often feeling like a villain in his own town once Jordan moved in.

“We all grew up Bulls fans,” Thomas said several years ago. “But my mom and my brothers … sometimes I would look up in the stands and see them clapping for the Bulls, and I’d be like, ‘What the hell? I gave y’all them tickets!’

“Your friends would tell you after you got them tickets, ‘I’m coming to the game, but you know we’re gonna beat y’all tonight.’ And I’d say, ‘I’m part of y’all, right?’ And they’d say, ‘No, we’re with the Bulls.’ It was nice to go home and just light it up because you knew after the game, if you lost, they were going to give it to you.”

Basketball took Thomas out of Chicago but nothing could take Chicago out of him. Some see his smile and on occasion wonder about his sincerity. But no one questions the authenticity of his trek from mean streets to posh boulevards across 50 years in the game.

Chicago might be the Mecca, but if you grew up the way Thomas did, getting out was better than getting “next!”

“What makes the journey special in Chicago,” Johnson said, “is navigating the games and navigating the peers that would try to get you to do something you didn’t want to do. To get past that and be smart enough to not get caught up in anything.”

That applied to the city more than players raised in the less-risky suburbs of Chicagoland. But eventually, all hoops roads led to the same place.

“There was never any prejudice in basketball in Chicago,” Johnson said. “If you could play, you could play. We judged you on that. And how tough you were.

“Could you deal with a really intense situation? We’d go into neighborhoods that weren’t the best, guys would get physical with us, elbows get thrown to where you’re going to have a fight. What do you do? Do you keep playing hard?”

In this town you do. Or you’re done.

* * *

Steve Aschburner has written about the NBA since 1980. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.