You can’t judge a Final Four contender by how many NBA prospects it has, anymore than you can rate the quality of an NCAA basketball program solely by how many professional players it has produced.

But just for the record, it’s worth mentioning on the brink of so much excitement in San Antonio this weekend that the Ramblers of Loyola University in Chicago are clear underdogs by NBA standards as well.

The other three schools that have reached the biggest stage in men’s collegiate basketball are widely known as powerhouses in that sport. And as one might expect with doctors from Johns Hopkins or sportscasters from Syracuse, Kansas, Michigan and Villanova boast some pretty impressive job-placement numbers.

Combined, those three schools — the Jayhawks (74), Wolverines (53) and Wildcats (44), oh my! — have sent 171 players to the NBA, its precursor, the Basketball Association of America, or the upstart American Basketball Association (1967-76). Their names are among the best known and most accomplished in the game, starting with James Naismith, the man who invented it and soon thereafter became Kansas’ coach and athletic director.

From Wilt Chamberlain to Joel Embiid (Kansas), from Cazzie Russell to Jamal Crawford (Michigan), from Paul Arizin to Kyle Lowry (Villanova) and beyond, the alumni lists of those three school have helped write the history — pages certainly, in some cases whole chapters — of the NBA.

And then there’s Loyola. And its 16 players who played professionally at the sport’s highest level, without having to grab their passports.

It’s a humble group, smaller among the schools just in Chicago than DePaul’s (35) or tweedy Northwestern’s (17). And fully half of the Ramblers gone pro were in and out by 1954, before George Mikan (DePaul) even retired.

Among them: Wilbert Kautz, Mickey Rottner, Jack Dwan and Jerry Nagel. Ring any bells yet? The one who made the biggest mark was Jack Kerris, a 6-foot-6 power forward who logged 271 appearances from 1949 to 1953 with Tri-Cities, Fort Wayne and Baltimore.

Kerris was the Ramblers’ first NBA draft pick (ninth, 1949 BAA) who served in the U.S. military during World War II before averaging 7.6 points on 36.3 percent shooting. As a group, those first eight Loyola products shot just 32.5 percent back in the proverbial day.

The second Loyola eight includes Jerry Harkness and Les Hunter, starters on the 1962-63 squad that won the NCAA championship; Andre Wakefield, Wayne Sappleton and Alfredrick Hughes from the program’s more recent past; and Milton Doyle, a two-way player with the Brooklyn Nets this season and the only Rambler to reach the NBA in the past 30 years.

Being called the worst draft choice and the biggest bust, I carried that on my back for a number of years. It used to hurt me when I didn’t get a chance to produce.”

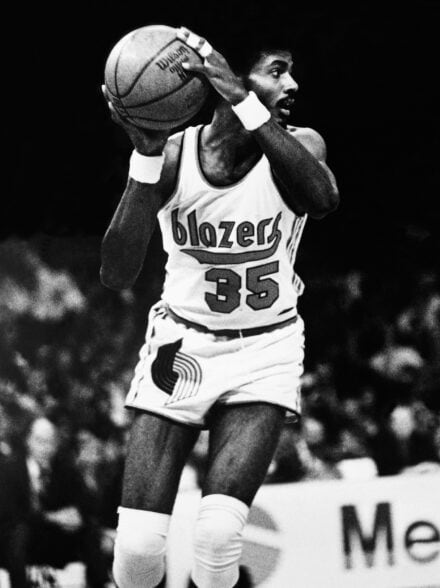

LaRue Martin, 1972 No. 1 draft pick

Harkness and Hunter are remembered primarily for their performances as two of the four black starters used by Loyola coach George Ireland back when that was considered unacceptable. As Tom Oates of the Wisconsin State Journal wrote this week, Ireland, a native of Madison, Wis., “was ahead of his time in the widespread use of black players even though it defied the gentleman’s agreement among coaches at the time: Play one black at home, two on the road, three if you’re behind.”

Harkness, a 6-foot-2 guard, was drafted in 1963 by the Knicks in his hometown of New York. He spent his rookie season with them before becoming the first black salesman for Quaker Oats. Three years later, Harkness wrangled a tryout with the ABA’s Indiana Pacers and played 81 games in two seasons before his knees gave out. He later was employed by the team, worked in sports media and became a civic leader in Indianapolis.

Hunter, a 6-foot-7 center, was drafted by Detroit and traded to Baltimore for an NBA career that lasted 24 games and 114 minutes in 1964-65. But the ABA came calling and Hunter wound up averaging 12.8 points and 7.1 rebounds for the Minnesota Muskies, Miami Floridians, New York Nets, Kentucky Colonels and Memphis Tams over six seasons. He appeared in 444 games and was a two-time ABA All-Star.

By sheer statistics, Hunter had the most prolific pro career. But the biggest name to come out of Loyola remains LaRue Martin, the NBA’s No. 1 draft pick in 1972. And his notoriety largely comes from what he wasn’t — Martin for five decades has been known as the biggest flop in draft history, or at least was until UNLV’s Anthony Bennett was selected by Cleveland in 2013.

“Being called the worst draft choice and the biggest bust, I carried that on my back for a number of years,” Martin said this week, too excited by the current Ramblers’ trek to the Final Four to dwell on his ill-fated pro career. “It used to hurt me when I didn’t get a chance to produce. But I kept my mouth shut. Why say anything negative?”

Martin earned his status as first player picked by averaging 18.2 points and 15.9 rebounds across three seasons for Loyola. But he struggled to help a bad Portland team (21-61), getting on the floor for just 12.9 minutes nightly for Trail Blazers’ coach Jack McCloskey. It especially galled Martin when the Blazers played in his native Chicago his rookie season. He had acquired tickets for family and friends, only to have McCloskey keep him planted on the bench the whole night.

“I cried like a baby but I didn’t let anybody see me,” the 6-foot-11 Martin said in a phone interview. “It bothered me but you have to hold things within you, because you have no control.

“But I’m 68 years old now. And I’ve got a ring — from UPS, for 30 years of service.”

Martin lasted four seasons in the NBA on a contract worth approximately $900,000. He went to work after that with Nike during its early growth years in Beaverton, Ore., and still was there when Michael Jordan arrived on the NBA scene. But a friend talked him into joining UPS, with the lure that Martin could transfer home to Chicago. So he switched — and started out by driving a UPS truck for the first six months.

Since then, Martin has worked at almost every level in the company, from a human resources manager to his current executive role dealing with the federal government and public affairs. He was a board member for the National Basketball Retired Players Association for six years and might run again, even while working at UPS well past his expected retirement age.

Martin’s life after basketball is what he thinks about in relation to his alma mater now. For every Donte Ingram, the Ramblers’ shooting guard with an outside shot as an NBA prospect, there are another dozen whose hoops careers will end when they leave Loyola.

“It’s good to push sports, but they need to push academics too,” Martin said. “Did you know they’ve got a graduation rate for athletes as good as Harvard University? There are a lot of things people are missing, in terms of selling this school. Sports can get you through a lot of doors, but where would I be today if I didn’t get my degree. I’d be back in public housing.”

Martin lives five blocks from campus on Chicago’s North Side and walks back there often. He stays in touch with old teammates such as Rich Ford and Isadore Glover, and has come to know the other alumni who have reached the NBA.

He had the offer of a ticket for the Final Four games Saturday but couldn’t sync up the air travel and hotel on short notice. So he might watch Saturday’s game against Michigan with students at the school.

“When it comes down to group therapy or whatever you want to call it, this team has it going on,” Martin said. “The key is, they don’t really have a so-called superstar. These young men play together. When they see the open man, he’d better be ready for a pass. And when the opposing team is taking a shot, guess who’s doing the blocking out. It’s all Loyola – the opposing team doesn’t get a second chance.

“I am very, very proud of my alma mater. It’s something that no one expected, but every day is a new day. There’s no homecourt advantage, and these young men are doing what they have to do.”

* * *

Steve Aschburner has written about the NBA since 1980. You can e-mail him here, find his archive here and follow him on Twitter.

The views on this page do not necessarily reflect the views of the NBA, its clubs or Turner Broadcasting.